general

You Don't Need a Native Chrome Extension (Until You Do)

@jfdelarosa

February 10, 2026

If you’ve ever built a Chrome extension from scratch, you know the feeling. The developer experience is stuck in a different era. No hot reload, clunky debugging, weird state management between background scripts and content scripts, and every small change means reloading the extension manually.

Compare that to modern web development, where you save a file and see the result instantly, and it feels like going back in time.

The first version of LunaNotes was a native Chrome extension. Built the “right way”, content scripts, background service workers, Chrome APIs, the whole thing.

It was painful.

I had an idea I wanted to validate, and the native extension workflow was slowing me down. So I made a decision that saved me months: I rebuilt the whole thing as a web app wrapped inside an iframe.

That decision took LunaNotes from an idea to 12,000+ users. Now I’m going native again. And both decisions were right, just at different stages.

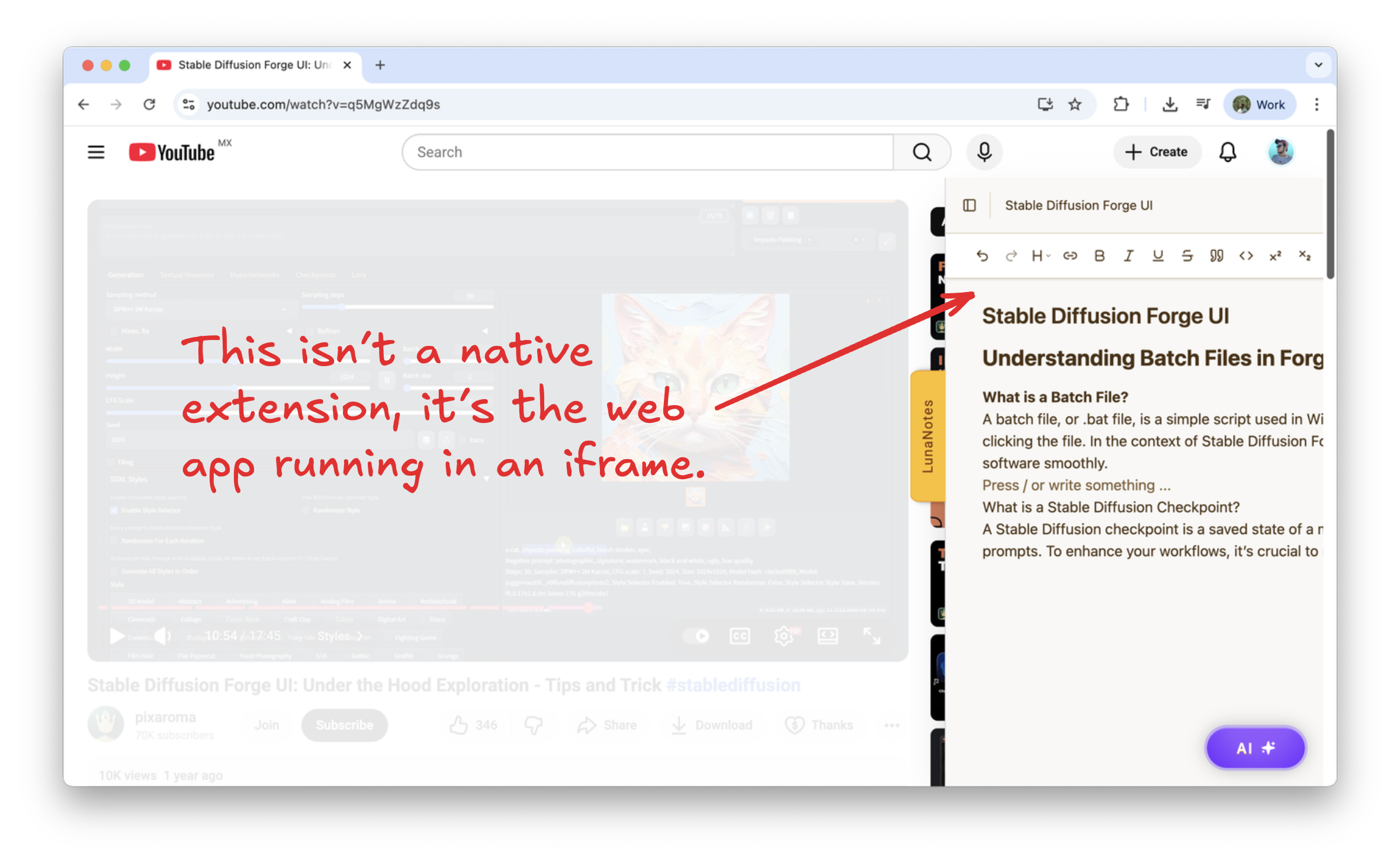

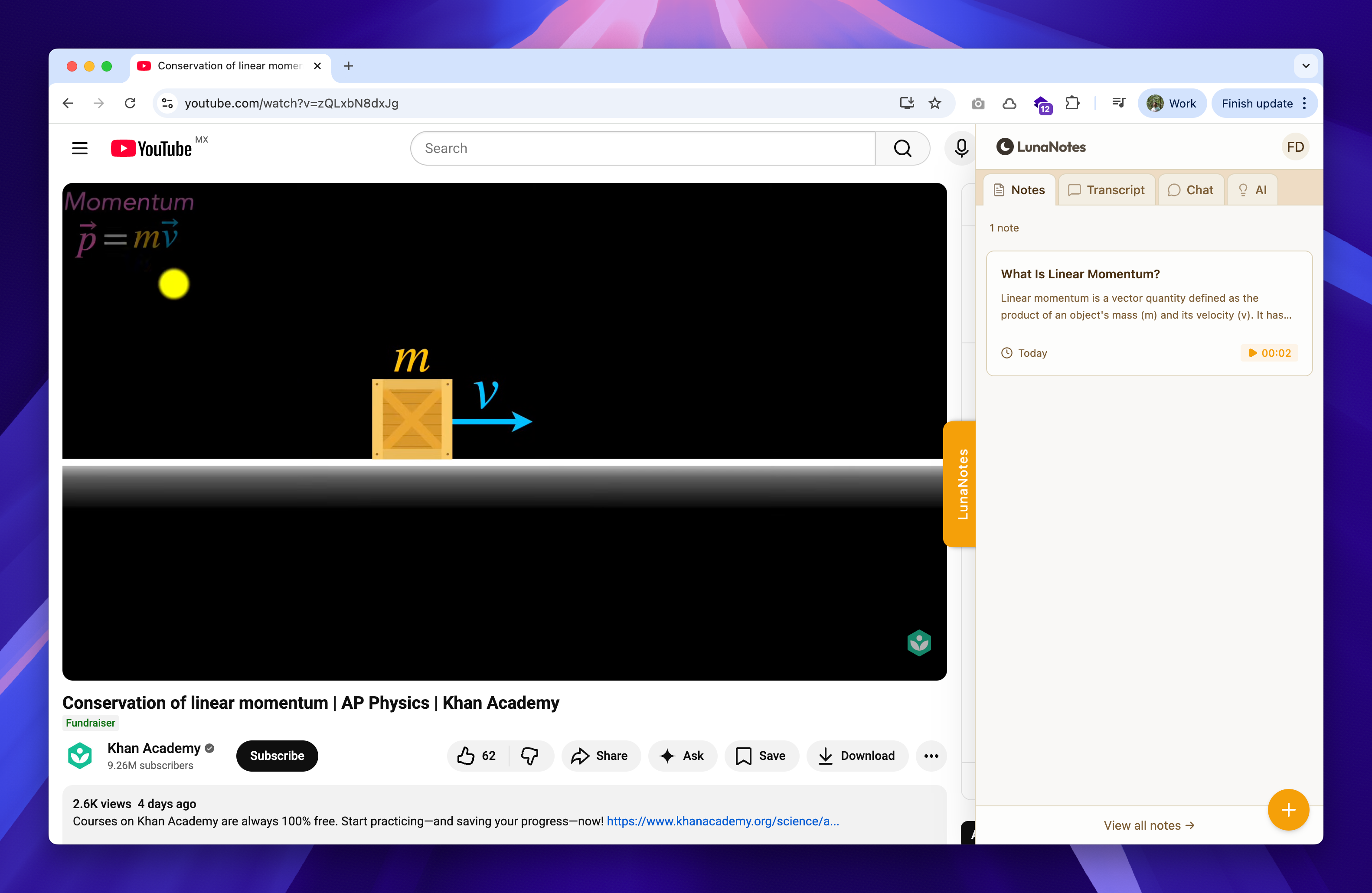

The original LunaNotes extension: a full web app loaded inside an iframe

If you’re used to building web apps with modern tools, Svelte, React, Vite, TailwindCSS, the Chrome extension development experience will feel like a step backwards.

Here’s what I was dealing with at the time:

No hot module replacement. Every change requires manually reloading the extension from chrome://extensions. Change a style? Reload. Fix a typo? Reload. It kills your flow.

Fragmented architecture. Your code lives in multiple isolated contexts, background service workers, content scripts, popup scripts, and they all communicate through message passing. It’s powerful, but it’s a lot of boilerplate for something that should be simple.

Limited tooling. You can use bundlers and frameworks, but they don’t feel like first-class citizens. The ecosystem is small compared to web development, and things that take minutes in a web app can take hours in an extension.

I was spending more time fighting the platform than building the product. And when you’re a solo developer trying to validate an idea, that’s a death sentence.

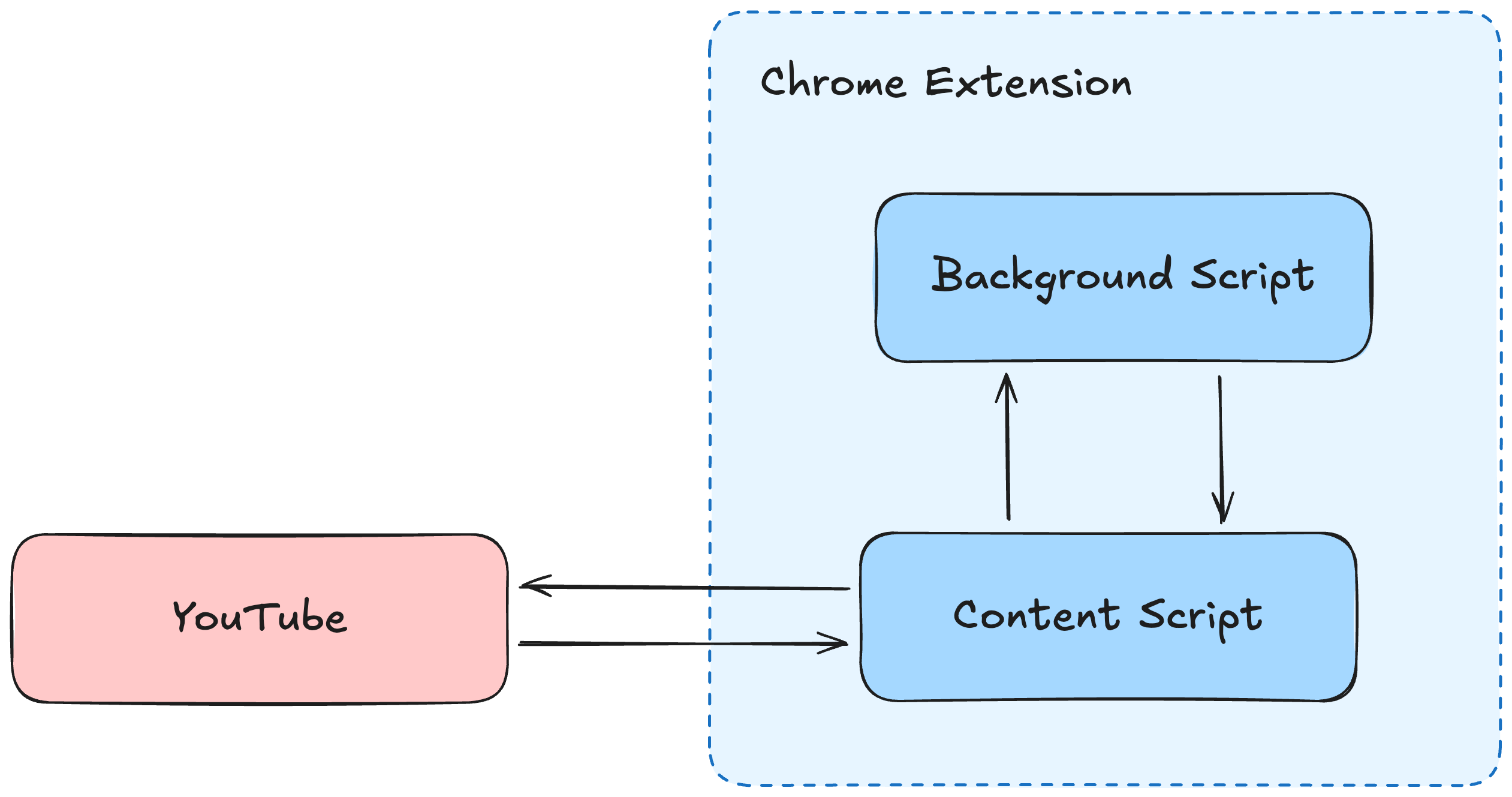

To understand why this is so complex, look at how a native Chrome extension actually works. When you visit a YouTube page, the content script injects into the page and extracts video data. But it can’t do everything on its own, it needs to communicate with a background service worker for things like making API calls, accessing Chrome storage, or handling browser events.

That’s three separate execution contexts (the YouTube page, the content script, and the background worker) all talking to each other through Chrome’s message passing APIs. Every feature requires careful orchestration between these layers, and debugging means jumping between multiple isolated environments with different debugging tools.

Native extension architecture: three isolated contexts communicating through Chrome’s message passing APIs

After weeks of fighting this architecture, I had a realization: a Chrome extension doesn’t have to be built with Chrome extension APIs. At its simplest, it can just be a shell that loads a web app inside an iframe.

Instead of the three-layer native architecture, I collapsed it into something radically simpler. The web app, built with SvelteKit, TypeScript, and TailwindCSS, would handle all the product logic: the rich text editor, AI features, note management, everything. The extension would do exactly one thing: inject an iframe that loads that web app into the YouTube page.

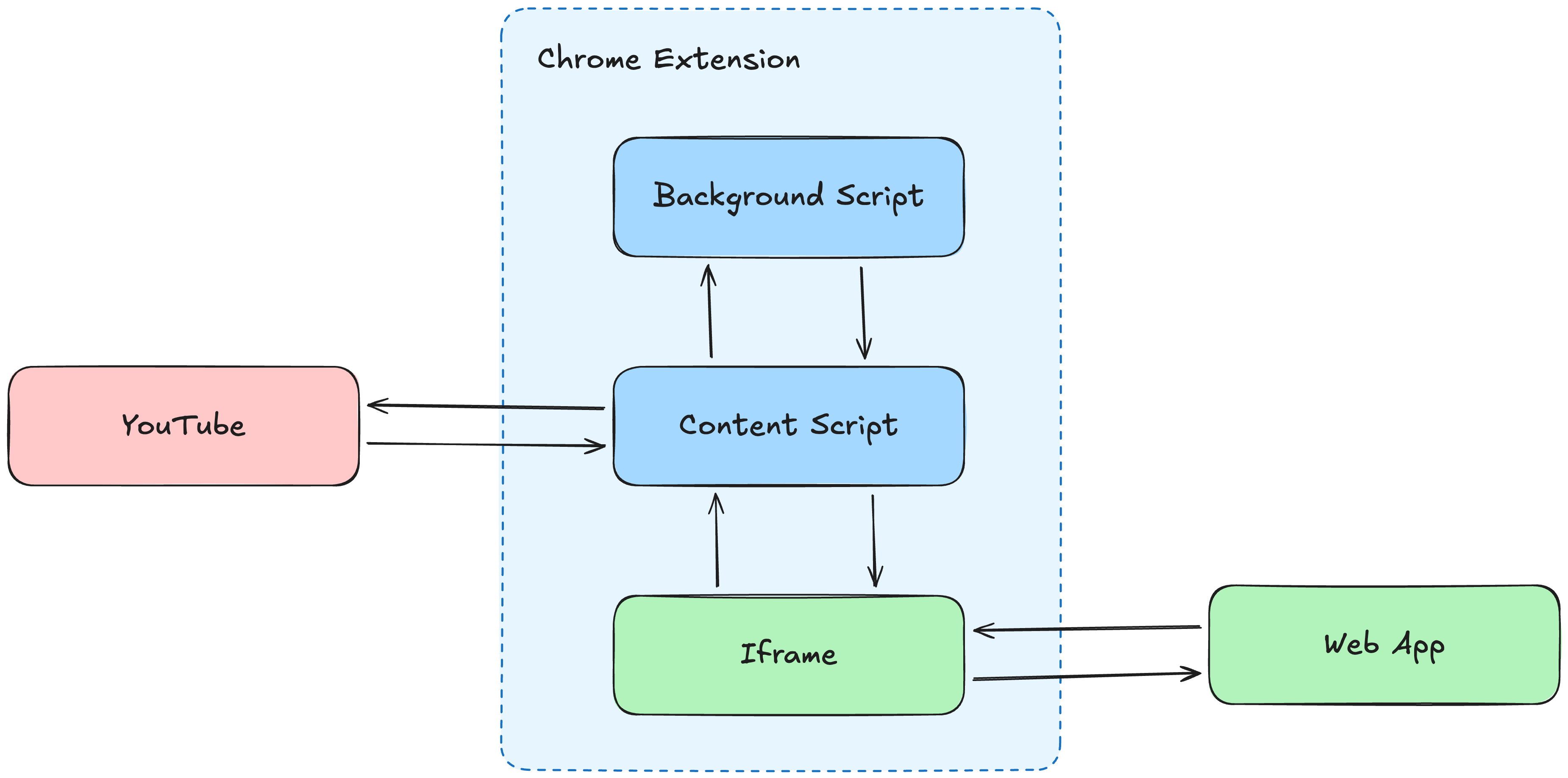

The diagram below shows how this changes the architecture. The content script still extracts data from the YouTube page, but instead of sending it to a background worker, it talks directly to the web app running inside the iframe using the postMessage API. No background worker needed.

Iframe approach: simplified architecture with direct postMessage communication, no background worker needed

The development experience here is essentially the same as building any modern web app. You’re using familiar tools, patterns, and APIs that every web developer already knows.

The extension layer now becomes almost trivial. Here’s the bare minimum code to inject your web app:

// Content Script - runs on YouTube page

// Create an iframe element that will host the web app

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe');

iframe.src = 'https://app.lunanotes.io';

iframe.id = 'lunanotes-panel';

document.body.appendChild(iframe); // Add it to the YouTube pageThat’s it. This code runs on every YouTube page and injects the web app as an iframe. The entire extension was maybe 500 lines of code, most of it was just CSS and positioning logic to make the iframe appear as a nice collapsible side panel. All the real product work, the editor, AI features, note management, happened in the web app.

The one thing you need to figure out is communication. The content script runs in the context of the YouTube page, and the web app runs inside an iframe. They’re in separate JavaScript execution contexts and can’t directly access each other’s variables or functions.

That’s where the postMessage API comes in. It’s a standard browser API designed specifically for safe cross-origin communication between windows, iframes, and other browsing contexts. Think of it as a message bus, one side sends a message, the other side listens for it.

Here’s a real example from LunaNotes: when a user starts taking a note, you want to pause the YouTube video so they can focus on writing. This requires coordination between the web app (which knows when the user is typing) and the YouTube page (which controls the video player).

Step 1: Send video data from the content script to your web app

// Content Script - runs on YouTube page

const iframe = document.getElementById('lunanotes-panel');

// Send a message to the iframe

// First parameter: the data you want to send (can be any serializable object)

// Second parameter: target origin (the URL of the iframe for security)

iframe.contentWindow.postMessage(

{ type: 'VIDEO_DATA', videoId, timestamp },

'https://app.lunanotes.io'

);The second parameter ('https://app.lunanotes.io') is important for security. It ensures only your web app can receive this message, not some other iframe that might be on the page.

Step 2: Your web app listens for messages and can send messages back

// Web App - runs inside the iframe

// Listen for messages from the parent window (the YouTube page)

window.addEventListener('message', (event) => {

// Security: verify the message is from the expected origin

if (event.origin !== 'https://www.youtube.com') return;

if (event.data.type === 'VIDEO_DATA') {

// Use the video data in your app

console.log('Received video:', event.data.videoId);

}

});

// When user starts typing a note, send a pause request

window.parent.postMessage(

{ type: 'PAUSE_VIDEO' },

'https://www.youtube.com'

);Step 3: The content script listens for pause requests

// Content Script - runs on YouTube page

window.addEventListener('message', (event) => {

// Listen for messages from the iframe

if (event.data.type === 'PAUSE_VIDEO') {

// Find the video element and pause it

const video = document.querySelector('video');

if (video) video.pause();

}

});You define a simple message protocol between the two sides, and you’re done. No background service workers, no Chrome storage sync headaches, no complex state management across extension contexts. Just two windows talking to each other using standard web APIs.

Once I made the switch to the iframe approach, everything changed. I went from fighting Chrome extension APIs to building a web app with all the tools I already knew:

Real developer experience. Hot reload, proper debugging, component-based architecture, all the things I was used to. I was building a web app again, not wrestling with extension APIs.

Ship once, update everywhere. Because the real logic lives in the web app, pushing updates is just a deploy. No need to submit a new version to the Chrome Web Store and wait for review every time you fix a bug.

Iterate at web speed. I could test ideas, ship features, and respond to user feedback in hours instead of days. For a solo indie hacker trying to find product-market fit, this speed is everything.

One product, two surfaces. The same app that powered the extension also worked as a standalone web app . Users could take notes on YouTube through the extension, then access everything from the web. One codebase, two experiences.

This approach got LunaNotes to 12,000+ users. But as the user base grew, so did the feedback, and it kept pointing in the same direction.

The extension feels too complex. Because the iframe loads the full web app, users were getting the entire LunaNotes experience crammed into a side panel. They wanted a lightweight YouTube companion, not a full app. The extension and the web app have genuinely different UX needs, and forcing them to be the same was hurting both.

Performance. Loading an iframe means loading your whole web app, styles, scripts, network requests, everything. On slower connections, there was a noticeable delay before the panel was ready.

Browser API limitations. There’s a lot you simply can’t do from inside an iframe. Reliable tab URL access, Chrome storage sync, alarms, side panel API, all of that requires native extension code.

CSP fragility. Some pages have Content Security Policies that restrict iframe embedding. YouTube has gotten stricter over time. You’re always one CSP update away from your iframe suddenly not loading, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

So now I’m separating the two. The web app stays as the full LunaNotes experience , notes, AI chat, diagrams, flashcards, everything. The extension becomes a lightweight, focused companion that fully leverages Chrome’s APIs for what they’re good at.

The good news: we’re not throwing everything away. We’re rebuilding the extension with WXT , a framework that brings Vite’s developer experience to browser extensions. The critical part is that we can import components and logic directly from our main web app codebase. The rich text editor, the note storage layer, the AI integration, all that code stays shared between the extension and web app.

What changes is the shell. Instead of an iframe loading app.lunanotes.io, the extension now renders native Svelte components that talk directly to Chrome’s APIs.

We get all the modern tooling we had with the web app: hot reload, TypeScript, and Tailwind. But we also get the native capabilities we were missing: chrome.storage.sync for cross-device data, the Side Panel API for better UX, and zero CSP anxiety.

The iframe approach bought us time to validate the product with real users. WXT lets us evolve the extension without starting from scratch.

The result is a native extension that feels significantly faster and more integrated with the browser.

The redesigned native extension built with WXT: faster, lighter, and fully integrated with Chrome APIs

Here’s the thing: building a Chrome extension is easier than ever now, especially with AI. Tools like Claude Code can scaffold a native extension or WXT project in minutes, and the quality is good enough to ship. If you’re starting fresh today, I’d always recommend WXT over raw Chrome APIs, the DX difference is massive.

For the LunaNotes refactor specifically, I used Claude Code in a loop to migrate components systematically. The agent would take a task, refactor the code to work natively, run tests, commit, and move to the next one. What could’ve been weeks of manual work became a structured, reviewable process.

I’d recommend the iframe wrapper approach if:

- You’re validating an idea and need to ship fast

- Your extension is mostly a UI that can live in an iframe

- You’re a solo developer and can’t afford to maintain two codebases

- You need to iterate quickly without waiting for Web Store reviews

Go native when:

- Real users are telling you the experience isn’t good enough

- You need deep browser integration (tabs, storage, alarms, side panels)

- Performance and load times matter

- Your extension and web app need to be different products

The best architecture is the one that lets you validate your idea before it dies. I started native, realized it was killing my speed, and switched to an approach that let me ship and learn. Now that I have users and real feedback, I can invest the time to build the extension the “right way”, because I actually know what “right” means for my users.

If you’re building a Chrome extension and you’re spending more time fighting the platform than building your product, try the iframe approach. You can always go native later, and you’ll do it with way more context than if you’d started there.